So, I had told myself I'd get use to Linux prior to coming to Red Hat, but truthfully that wasn't much needed. You learn fast when you're thrown in, and its sink or swim.

So, Fedora 16 was my first Linux distribution. I liked it a lot. I liked GNOME 3 a lot. With Fedora 16's end-of-life approaching (today, in fact) it was time to jump ship. GNOME 3 was nice enough, but I decided to put some of the noise about it in perspective and try something else.

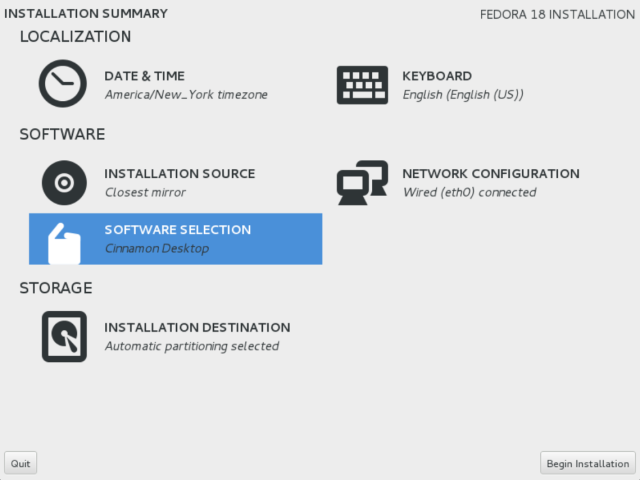

Installing

Noticeably worse - a bit sad because obviously a lot of work was put into it. The new layout shows you all your options at once, but I think stepping you through them was more user-friendly. Partitioning was confusing but in the end, it all worked well. Once I figured out I had to click on my F16 install, and hit a 'minus sign', everything went smoothly.

GNOME 3.6 Visuals, Graphical boot loader, etc

This probably impressed me more than it should have, but everything looked really tight to me. The fedora boot loader has a graphical back-drop, the login screen looks really nice, as were the various GNOME3 visual improvements. All of it fit together really nicely. Of course, at the end of the day, I would happily turn off any of these things for a better workflow. It sure is nice when people ask 'Whats this Linux thing?', and you have something shiny to show them.

Bugs

So once I tried to get some real work, I was unhappy to find a lot of small Eclipse issues. While F18 can only be blamed for bugs in Eclipse to a limited extent, it is one of those 'too big to fail' applications these days, so its worth mentioning. Without going into detail, these included issues with Java perspective not showing up after installing Eclipse Java Tools, and various graphical glitches using Eclipse C++ Tools. A more fundamental bug occurred when I tried to turn on desktop icons in GNOME 3.6 - instant crash, and crashing whenever I logged in.

Cinnamon!

The best thing about failing to get icons working on GNOME (admittedly I didn't try hard) was the decision to try out if they worked with Cinnamon. First off, I was very impressed with how well Cinnamon integrated with the whole Fedora user experience. Not only did a single yum command and a 'cinnamon --replace' have me trying it out in seconds flat, it was very simple to make my default desktop environment (toggle on log-in).

For someone like me that found GNOME 3's visually appealing, Cinnamon was perfect. Very soon I got rid of that 'hot corner' that GNOME 3 is so centered on, and set up some settings to my liking. Overall I find it more featureful, perhaps more Windows-like, but I'm not complaining.

Some things I do miss though is the nice way of dragging windows into workspaces with GNOME 3, and the 'application-centric' alt-tab that groups windows based on application.

Anyway, that's it for now. Overall I really like it, but then again I would have just been happy to get up to date packages again. YMMV.

Tuesday 12 February 2013

Saturday 2 February 2013

A Lesson from Java's Swing

So whenever possible, I like to apply things I learn in my hobby programming to my professional programming. Conversely though, sometimes I am inspired by the design of parts of icedtea-web (the project I work on at Red Hat). To be fair, this is more the design of Java's Swing library, but it got me thinking.

The menu code in Lanarts was pragmatic but also hackish. It piggy-backed the normal event loop and each menu was a pseudo-level. That meant there was a bunch of classes that inherited from GameInst that were only part of the menu code. The menu code was created based off these objects being planted into the pseudo-level, configured with callbacks to wire the menu logic and drawing, and just enough menu placement logic code so that things were spaced sanely on different resolutions.

1. InstanceLine:

The GameInst structure was abandoned as well, and instead a simple event loop was created in Lua.

It was really fun to code, and ended up being a large improvement. Here is a picture of the result with debugging code turned on:

Note this looks exactly like it did before -- not bad for a complete reprogramming in Lua!

The elegance with which it could be programmed made me feel a lot more confident in Lanarts ability to act as an effective moddable engine. I was able to code it in Lua with only take very brief breaks to quickly add a missing function or two on the C++ side.

One surprising inspiration I got is to have a similar mechanism for the level generation. A nested tree of randomly generated layouts could produce very interesting results!

The menu code in Lanarts was pragmatic but also hackish. It piggy-backed the normal event loop and each menu was a pseudo-level. That meant there was a bunch of classes that inherited from GameInst that were only part of the menu code. The menu code was created based off these objects being planted into the pseudo-level, configured with callbacks to wire the menu logic and drawing, and just enough menu placement logic code so that things were spaced sanely on different resolutions.

Taking a Swing at a better design

Although it wasn't the first time I used Swing, recently while having to assemble a dialogue box with nothing but Swing layout managers, it struck me that this could be a good approach for Lanarts user interfaces. While Swing has a large number of obscure layouts, a comment struck me that I forget the source of: "Using GridLayout and BorderLayout you can create pretty much any interface". So I coded the equivalent of these in Lua. This resulted in two small classes:1. InstanceLine:

Arranges objects in rows, this is similar to Java's GridLayout, but is designed to be especially convenient if you just want a single row.2. InstanceBox:

Objects are added based on relative position; a value 0 to 1 is used for x & y coordinates. Using this layout you can easily align something against the center-top of a box, and another component on the center-bottom, for example.Using these classes nested together, flexible layouts can be created with a lot less mucking around with coordinates. The x & y positions of each menu component are now calculated each time they are drawn, instead of being fixed absolute values. This allows each layout to only store relative positions, making logic simpler. As well components can be created without their locations having to be known at the time of creation.

The GameInst structure was abandoned as well, and instead a simple event loop was created in Lua.

It was really fun to code, and ended up being a large improvement. Here is a picture of the result with debugging code turned on:

Note this looks exactly like it did before -- not bad for a complete reprogramming in Lua!

The elegance with which it could be programmed made me feel a lot more confident in Lanarts ability to act as an effective moddable engine. I was able to code it in Lua with only take very brief breaks to quickly add a missing function or two on the C++ side.

One surprising inspiration I got is to have a similar mechanism for the level generation. A nested tree of randomly generated layouts could produce very interesting results!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)